Good friction

On incentives and opt-outs.

A shorter dispatch today with some reflections from an event I attended last week. Relatedly, I’m delighted to report that the massive Juju Vera-esque vintage brooch I wore to the conference made it not once, but twice through TSA in my carry-on. Recommend!

Last week, I was invited to a breakfast with Kristen Berman, founder and CEO of Irrational Labs and host of Product Teardowns, where she shared how she works with clients like Uber, Microsoft and LinkedIn to create user stickiness. Since this was a healthcare crowd, she gave the example of TytoCare, the at-home medical exam kit you pair with a telehealth visit to send clinicians things like an image of an ear infection. The company noticed the devices they sent to users often went unopened and unused (their sensors even picked up on the fact that they were often cold i.e., left in the garage).

Source: TytoCareThe real barrier wasn’t need; it was setup. At first, Kristen’s team contemplated a phone support line. But the problem was getting the user to call. So instead, they leaned into the endowment effect: we value what we believe is already ours, and we especially value what we think we might lose. TytoCare let customers know that if the device wasn’t activated within a certain number of days, it had to be returned. And it worked.

Whether it’s devices or limited-edition Lalabu drops, consumers respond to good friction. It’s the line wrapped around the block for Anthropic’s Thinking Cap (I kind of want one to wear ironically, but as a knowledge worker, does that make me in on the joke or part of the punchline?). It’s weight-loss coaching platform Noom’s intentionally long sign-up flow that takes fifteen to twenty minutes, which Kristen gave as another example. Partly, Noom does this because they want to get to know you; partly because they want you to prove you’re willing to complete what is arguably the easiest step of their journey. The friction is the commitment.

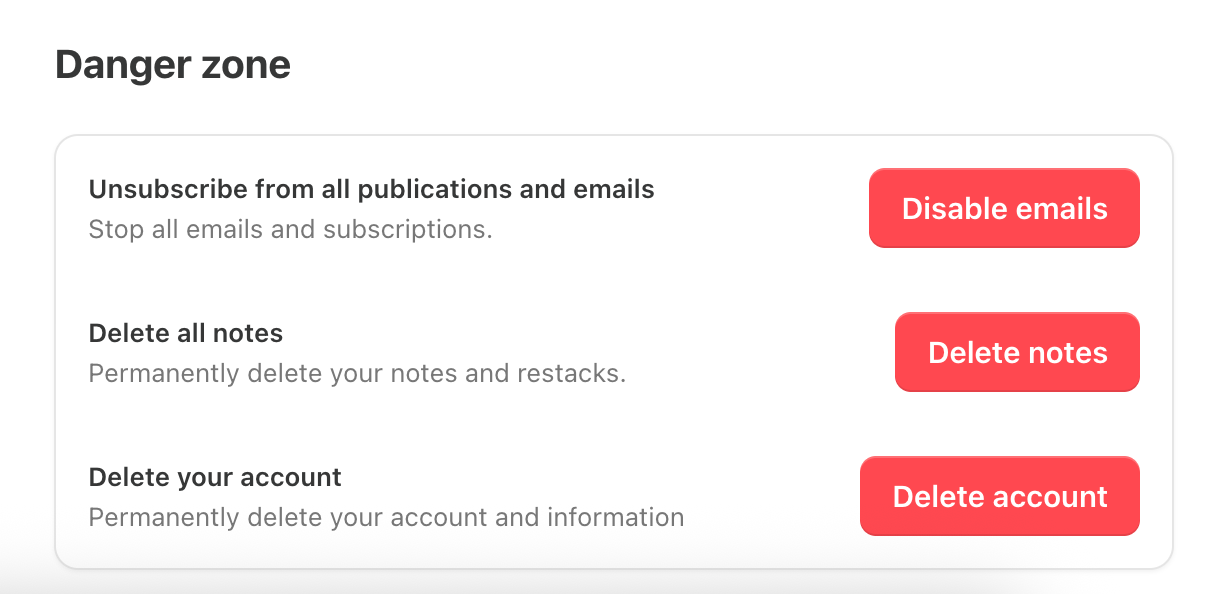

Where companies often go too far is in the opt-out. Unsubscribing is one thing: low stakes, low loss—it’s usually not that hard to do. Deactivating an account is a different thing. Deleting an account and losing data is different again.

On this last point, I actually understand why some platforms make that moment feel serious. Substack labels data deletion as a Danger Zone so you know the stakes: your content is gone. Others, like Twitter/X, trigger a deletion process that runs for a set number of days so you can change your mind.

Cue the 80s soundtrackWhen I think about bad friction, I think about choice architecture that works against me when I’ve already made up my mind and the stakes are essentially zero. A meal-kit subscription. A vitamin delivery. The process is often onerous: the button hidden somewhere counterintuitive, the cascade of “Are you sure you don’t want to snooze instead?”, the last-ditch 20% discount, the exit survey. It rarely makes me reconsider my choice; it just makes me avoid coming back because I don’t want to go through the gauntlet again.

What’s interesting is that, in a culture built on instant gratification, we respond really well to the right kind of friction, especially when desire is mediated by others. Mimetic desire is wanting something because someone else’s wanting made it legible. Noom lands better when I’ve watched a person I trust—maybe a friend, maybe an influencer—go through it. Anthropic’s Thinking Cap feels more meaningful when there’s scarcity at play and people waiting in line (Amy Odell has some interesting thoughts on how this relates to sample sales in her recent post about The Row). Good friction accrues meaning through shared validation.

We don’t resist effort; we resist effort when our minds have already been made up. Good friction says there’s something here. Bad friction says you don’t get to choose.

Some questions we should be asking as marketers (👋), founders and product designers include:

Am I helping my customer make a choice?

Do they believe it’s their choice?

Who or what is influencing that choice?

Am I helping them act on it, or making it harder?

Am I trying to persuade them, or dissuade them?

Personally? Give me the carrot and a yardstick — something to reach for and measure against — instead of the stick.

To quote the marketers at Anthropic: Keep thinking,

Claire

Great summary!